Preserving Dunbar: The Option to Purchase

The Lexington City Schools Board of Education’s decision in 2006 to build a new school has become entrenched in controversy. {Davidson Local/James Kiefer}

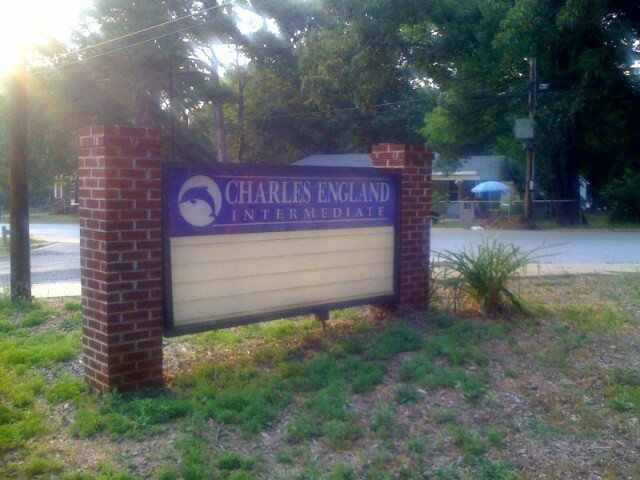

In 2006, the Lexington City Schools (LCS) Board of Education voted to build a new, state-of-the-art school on Cornelia St. The new Charles England Intermediate School (CEIS) would be housed on the property that was previously home to Eanes School.

The school relocated from the building on Smith Ave. that was once home to the city’s all-Black high school, Dunbar. Built in 1951, the school needed renovation and upgrades. After determining it would cost approximately as much money to renovate the school as it would to build a new one, the board opted for the latter.

As part of the decision making, the board restored the name of the building to Dunbar. It was changed in 1999 to honor the life and legacy of Lexington Senior High School and Davidson County Hall of Fame inductee, the late Charles England, a longtime educator, coach, activist and the creator of the LCS motto, “Be Somebody.”

CEIS, which has since been renamed to Charles England Elementary School, opened in 2008. With no immediate plans for the school, a decision had to be made.

Brainstorming

Conversations amongst the community began as early as 2001 regarding the needs of Dunbar. During that time, the late Rev. Dr. Ronald B. Shoaf and Charles Owens, a Dunbar High graduate, began having their own discussions. They anticipated a possibility the system would depart the school at some point. To be prepared, they began brainstorming ideas for the building.

“Shoaf felt we needed to have an alternative to the existing school system that was teaching our kids,” recalled Owens. “He wanted to have a private school or at least a charter school.”

In their research, they learned from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction there were only 100 charter schools allowed at that time according to the general statute. The chances of them being able to proceed with their plan were slim.

So, they switched strategies. Once they learned of the board’s choice, they began to focus on doing what was necessary to ensure the school wasn’t destroyed.

“I didn’t want to see what happened to the 4th St. School [it was demolished] happen to this one,” Owens said.

A Call to the Community

Jonathan Bush was a few years removed from college at North Carolina A&T State University when he was asked to partner with a coalition of citizens interested in securing funds to purchase Dunbar School. Bush, a former city planner with the city of Lexington, recalled meetings starting in either 2005 or 2006.

“My role, primarily, was being a consultant,” Bush explained. “Initially, it was a unified and concerted effort to acquire the building for future use. My goal was to get the team to hone in on what they wanted that future use to be.”

The CEIS sign remained outside of the building until 2014. {Contributed photo/Charles Owens}

According to Owens, who was a member of the LCS Board of Education when the decision was made to build the new CEIS, the system was willing to sell the building for $75,000. The group devised a plan.

Pride for Dunbar ran high in Lexington. Even though neither of the original buildings had served to only educate Black students in decades, many graduates gathered yearly for a reunion where they caught up on each other’s happenings, laughed and reminisced about their school days. Those who attended the schools were often seen wearing Dunbar shirts around town.

Having experienced the atmosphere firsthand, the collective believed they would encounter very few roadblocks in their quest to obtain the resources needed. They were met with the opposite.

“Unfortunately, I was shocked,” Owens confessed. “It was a great opportunity and I thought the Black ministers would get involved and come up with the funds to do it.”

Their attempts to talk to ministers individually were ineffective so they adjusted their approach. They were granted time to present their plan to the ministers at their monthly association meeting. Owens shared with the clergy why they felt it was necessary to step in and procure the school.

“They gave me 15 minutes to do my presentation and I told them we had one year to come up with $75,000,” Owens noted. “One thing I asked before I left is what is the mission of the ministers association. I think they got a little upset. It was a good question to ask.”

For a year, the group put out a plea to the Black churches and the community to help them acquire funding. For a year, they were met with little to no response. Marquia Shoaf witnessed up close her father’s dedication to the project despite the circumstances.

“I remember nights I would go to sleep and Daddy would still be up with his papers,” Marquia recollected. “Sometimes he was on the phone talking to ‘Bear’ [Owens] and whoever. They spent a lot of time on that phone. He was passionate about it. He was passionate enough to go to churches, reach out to people in the community for help and have a lot of sleepless nights. We had a lot of eye rolling conversations about it. It would consume our dinners and our free time. It was so near and dear to him.”

Bush recalled a lack of focus regarding the plan.

“The challenge I saw with the groups that were trying to get together is no one wanted to talk dollars. Many of the people wanted to reminisce about the great times.”

Sensing a need to make a move to protect the integrity of the structure, Owens and Shoaf collaborated for a year before submitting the necessary documentation to the North Carolina Office of Cultural Resources asking that the Smith Ave. building be placed on their study list for a potential historic designation. Their request was granted. As a result, the building cannot be torn down or altered.

Currently, many windows and doors are adorned with plywood at Dunbar School.

{Davidson Local/Kassaundra Shanette Lockhart}

With the collective unable to muster up the necessary dollars needed to purchase the school, LCS sold the building to the Catholic Diocese of Charlotte in 2009 for $100,000. As the building changed ownership, a bitterness arose amongst many.

“That put a sour taste in many alums’ mouths as to how the city of Lexington and the local school board chose to dispose of Dunbar,” said Bush, now a senior urban planner with the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. “They felt they should’ve been approached before it was sold. As a professional dealing with urban planning, I’m always ambivalent to that because I understand how local government budgets work. I do think from a historic nature historically African American schools are looked at more as liabilities versus cultural assets. In African Americans’ eyes, it’s seen as an asset. For people who work with local budgets, it was seen as a liability. As a professional, I clearly understand when a city or school board is looking to manage its budget they do have to look at where we can cut costs. It looked like Dunbar was costing them money and they couldn’t make any money off the school. There were no parties that came to the table that were able to secure that building.”

The lack of movement forward devastated Shoaf.

“He was literally sick to his stomach from the disappointment of it being sold from up under them because there was really no community support,” Marquia lamented. “The most frustrating part for him was that the community seemed to not care.”

After the sale, the group entered discussions with the Diocese about purchasing the school. Although they were still unable to acquire it, they kept an open line of communication that was used to express their displeasure in the organization’s proposed senior housing.

Reflecting on Previous Steps

Now that she is older, Marquia shared that she has grasped comprehension of her father’s passion for wanting to save the school.

“I see it differently now because I understand the importance of preservation of a community for us as a people. So much of our history is lost. There’s so much history there that I didn’t understand until I took the time to sit down and have him explain it to me. He told me how they weren’t allowed to go to other schools. This is the only place they were taught and educated for decades. He talked about how much he respected the teachers there and how they encouraged black students to persevere.”

With a plan, that has been met with opposition by neighbors in the community, in place by Shelter Investment Development Corporation to convert Dunbar into affordable, senior housing, Bush noted steps the city can take when citizen concerns arise again.

“A site planning process could’ve addressed a lot of the comments citizens had at the [public] hearing. They were talking about traffic, lighting, trash. They were making very valid concerns but the laws didn’t state that a project of this magnitude had to go through a site planning process. The laws didn’t state that when a developer comes in proposing something of this magnitude that they must give the community notice in writing so many days before the hearing. The jurisdiction I work in, when a developer wants to come in, they have to meet with the residents before they even submit their application.”

Although he’s disappointed in the outcome, Owens is happy there currently seems to be an attainable resolution regarding the future of Dunbar.

“I never wanted housing at all. I have mixed emotions because a lot of people don’t understand how housing works in America. It’s the number one revenue builder.”

Owens also wanted to address the accusations that he received payment in exchange for supporting the current plan for the school.

“I got nothing. Nobody greased my hand. After 20 years of trying, I’m glad someone is doing something with the building. Nobody else bought it or had a plan. Why knock it when you don’t have a plan of your own? We have to come to the table with something instead of complaining.”

Note: Per LCS Assistant Superintendent Emy Garrett, all LCS employees who were involved in the sale are no longer with the system or have retired. Therefore, no comment was issued by the school system.

Note: City of Lexington is currently working on updating its zoning ordinance. Information regarding changes that are expected to be made can be found here - https://www.davidsonlocal.com/news/dunbar-school-the-city-council-vote.